Friendly, observant, spirited, humorous, and refined: Serge Lutens comes as close to what one might call a Zen master of perfume as you can get. Enjoy our conversation with him about love, life, death, his admiration for women and, of course, perfume. As a filmmaker, hair & makeup artist for Diana Vreeland’s VOGUE, creator of Christian Dior’s first makeup line, creative director for Shiseido, and the mastermind of his 15-year-old eponymous perfume label, Serge Lutens has had more successful careers than one could ever hope for in a lifetime. Yet it wasn’t a fast-talking jack-of-all-trades type we talked with at length in Paris. For him, love, life, death, art — it’s all one. Add to that his passion for Morocco and Japan, his admiration for women, and, of course, perfume and you will see why when he talks, we listen. www.sergelutens.com

La Religieuse — The Nun.

Helder Suffenplan: Serge Lutens, your new perfume is called La Réligieuse — The Nun. This name led me to expect something unyielding and severe, so I was surprised to find the perfume is in fact soft and calming.

Serge Lutens: Merci. I don’t know what else to say, other than thank you. For to accept a compliment is the most difficult thing of all. To make compliments is an art, of course, yet to accept them is an even higher art form.

HS: Does my impression reflect your personal experience of nuns?

SL: Nuns for me are like snow: there is always something astonishing and magical about a pure blanket of snow yet it simultaneously provokes in us the desire to walk all over it and thus ruin its perfection. These two aspects are irrevocably conjoined: the image of a magic and almost, immaterial woman — the nun — and the urge to hurt her.

So who is the nun? At root, she is no one but myself, for the figure of the nun has actually accompanied me since the moment of my birth. My mother had a terrible time with me in labor: she suffered for three whole days. I didn’t want to come out — or perhaps she didn’t want to let go of me. And the circumstances back then in 1942 were truly dire. My mother was terrified by what would happen after the birth, for she was an “adulteress” and the law at the time condemned such women to prison and took their children away from them. Most men were either at the front or in POW camps while the women were left all alone at home. Very few were able to bear the loneliness of it all … And once I was born the nun snapped at my mother: “He’s the fruit of your own mischief and now you must pay the price!”

Habits from St. Catherine’s Hospital in Paris, Christian Friedrich Schwan, 1791. Photo: www.zvab.com.

Habits from St. Catherine’s Hospital in Paris, Christian Friedrich Schwan, 1791. Photo: www.zvab.com.

“Cruelty is part and parcel of life and beauty.”

HS: That was very cruel.

SL: Cruelty is part and parcel of life. There’s no escaping it. It is even part and parcel of beauty.

When I was about ten years old I spent some time with my mother in the Pyrenees and there was a canal there, on the bed of which were water weeds that swayed in the current like human hair. My mother said, “Wait here. I’ll be right back.” I knew it would take some time since she never came back straight away and so I made to sit down on the canal bank; but like a sugarcoated cake at a baker’s, a stone I stepped on was covered in an almost invisible spray — so I slipped and fell into the water.

I can still recall exactly, how I felt as I sank among those algae: like a man diving into a harem. Green fronds were swaying all around me and I felt a little like a frond myself [laughs]. All that with my eyes wide open! I almost drowned. I was unconscious by the time someone dragged me out. But I didn’t die, as you can see. I was rescued. And the first thing I said when I came around and opened my eyes was, “How wonderful that was!”

HS: Words that must have horrified your mother?

SL: Yes, but not enough to ever make her come back more quickly when she left me all alone [laughs]. I have the impression that she was always far away. Perhaps it is on her account that I constantly invent women in the form of perfumes or pictures. I am very grateful to her for that and yet, at the same time, I trample her like snow. These two feelings are very closely intertwined: a love of snow and a desire to trample and sully it. One can never love without paying the price: love always comes up with a bill.

HS: So the perfume conveys these two contradictory aspects of love?

SL: It is very ambivalent. It contains jasmine, as white as snow. And I also used civet, which is a secretion of the eponymous exotic cat and hence intensely animalistic. So it has these two elements: the floral, pure and extremely light note that floats on the air like snowflakes and the more predatory, earthy one. These two elements reflect the ambivalence I feel for the figure of the nun: the white surface one dare not sully and then my rage, crying out to do so. Which is also rage against my own life — against the very fact of being alive.

Yet to step upon and sully the snow would be to step on my own toes too, so to speak; for, in a certain sense, I am the mirror image of this image of womanhood and of the circumstances under which my existence was forged. Such ambivalence is a complex matter. And this perfume leaves behind a trace of ambivalence wherever it goes: the sweetness and delicacy of jasmine combined with animalist civet. The latter accentuates the jasmine to the hilt and thereby imbues it with immense vitality.

Monastery Graveyard in the Snow, Caspar David Friedrich, 1818/1819. Via: www.wikipedia.de.

Monastery Graveyard in the Snow, Caspar David Friedrich, 1818/1819. Via: www.wikipedia.de.

“The nose is a fine judge.”

HS: What is it that so fascinates you about perfume as a medium?

SL: The nose is a fine judge. The sense of smell enables us to feel mistrust and to ask ourselves: “What exactly is this?” The sense of sight has a similar function but olfactory perception is much more acute. Olfactory cells are renewed every twenty days and are the only cells in the human body to remain intact from the first until our last dying breath. And there is a reason for that! Despite the fact that most people today assume the nose serves nothing but the consumption of perfume [laughs].

Objectively speaking, a perfume is simply a compound of alcohol and other ingredients used to create something pleasant. In subjective terms, however, it represents the tension between things I could never express in words or images. Or at least cannot yet express: for one does after all manage, over time, to unearth and share ever more parts of one’s secret self.

Today, if one finds a smell unpleasant, one can simply walk away from it. That was impossible in earlier times. When I was small I really disliked the smell of manure but I eventually learned to like it, because I had no other choice. And life in general is no different: it is often the things we, initially, most emphatically dismiss that ultimately appear to us most compelling and vital.

HS: Because they say something about our deeper selves?

SL: In dismissing them, we dismiss ourselves! And that is the theme of La Religieuse: to find ourselves again by confronting our own ambivalence, our own duality.

“We unwittingly create our own selves.”

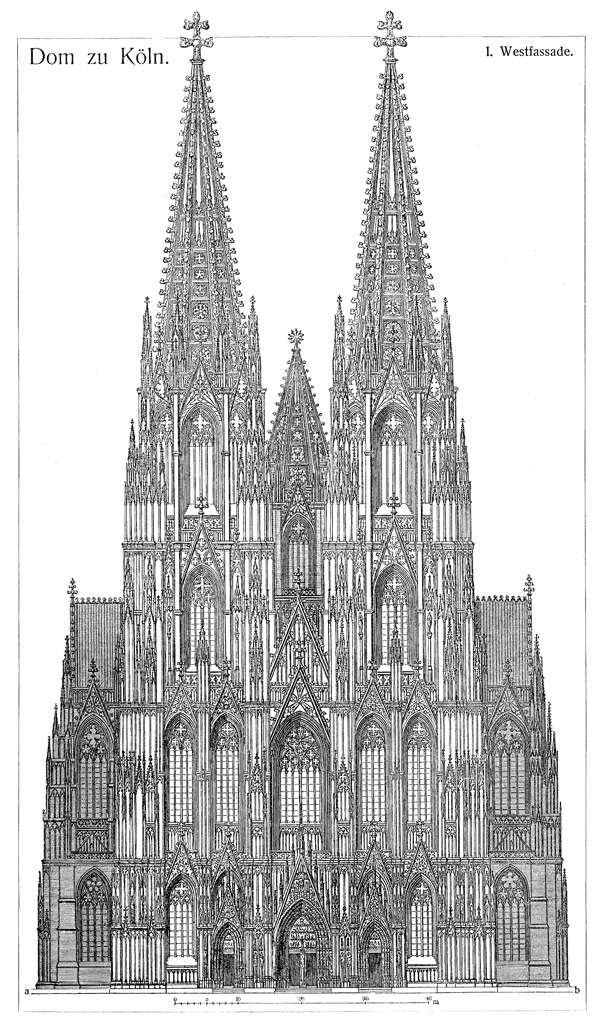

HS: The color of the liquid perfume is purple. Since I am from Cologne, a deeply Catholic city …

SL: … With a wonderful cathedral, the loveliest one in the world, and which escaped wartime devastation by only a hair’s breadth!

HS: … So I know that purple stands for suffering in the Catholic color code. It is the color of Lent. Did you have this in mind when you chose the color?

SL: Purple does indeed have something mysterious and religious about it. Along with black and white it’s the color I most prefer to wear — practically a second skin, in fact. It lies between red, the color of love, and blue, that of death. I never consciously chose purple as my favorite color. Rather, it was one of those completely unconscious decisions of the sort we reach in early childhood and which prove to be forever crucial. For the repercussions of such unconscious decisions never cease to shape our lives. Thus we unwittingly create our own selves. I am now seventy-two years old and perhaps it is high time I jumped over my shadow, so as not to become my own grave [laughs].

Cologne Cathedral, west facade. Image: original scan by the author.

Cologne Cathedral, west facade. Image: original scan by the author.

“My two passions: love and mysticism.”

HS: Does the white of snow likewise have something to do with death? As in, snow robs the world of all its color and swallows up all of its sound?

SL: And it blurs contours. Everything looks different under snow. Snow creates its own white and silent universe where nothing exists but the snow and oneself. That is why I use snow as a metaphor for my ideal of womanhood. But to love an ideal is extremely dangerous. I have done so all my life long: loved women, defended women, and mistaken myself for them too. And it’s possible that I no longer even know what the word love is supposed to mean, or what it means to love. It seems I am alone in this predicament; everyone else evidently knows what love is [laughs].

HS: Certainly, everyone appears to be looking for love.

SL: It is so difficult to define what love is. It means something different to everyone. If love means sacrificing a part of yourself on behalf of another — then love is no stranger to me. It is a sort of passion. Today, the term passion is bandied about a great deal: one can have a passion for wild strawberries or the like. I personally know only two passions, for love and for mysticism; and hence for the Passion of Christ, which implies devotion, sacrifice and surrender.

There’s a film with the title A Dangerous Method. The main character is Sabina Spielrein, a patient of C.G. Jung and a student of Sigmund Freud. She initially goes to Jung for psychotherapy and the two of them end up having an affair, which of course is not really permissible in a therapeutic relationship. Afterwards, she turns to Freud for further analysis. Spielrein contributed significantly to the development of psychoanalysis and also made a major discovery: namely that there is a death component to love. By this she meant the death of one’s personality; the renouncement of one’s existence; and the dissolution of one’s ego.

One cannot help but notice, by the way, that all the major psychoanalysts were German — or Austrian; which is perhaps in itself an interesting theme for psychoanalysis [laughs].

“Already as a young man, I fell for German Expressionism.”

HS: Germans evidently have a particular foible for anything unfathomable or concealed.

SL: You have a pronounced sense of that aspect of reality. Expressionism and Expressionist cinema likewise emerged in Germany. To my mind cinema and German cinema are one and the same thing: there is only German cinema. And Expressionist cinema is just magnificent.

HS: Actually, many Germans would claim that cinema is essentially French: René Clair, Melville, Truffaut …

SL: … Robert Bresson, Carné. Yet when I see the work of Michael Haneke, well, that is really something else again. I salute the man! The White Ribbon is a masterpiece! I don’t think I ever before saw : such a brilliantly directed cast. The film is so incredibly precise! And Haneke is a great admirer of Bresson, by the way. Of course, Haneke is Austrian. But he’s part of the German culture, after all.

Germany has always held great appeal for me. Already as a young man, I fell under the spell of Expressionism, was fascinated by its imagery and the violence of it. Germany has given me a lot and is a part of my history. You Germans were here in France when I was born and I guess that must be inscribed in my soul in some way.

HS: What distinguishes German art from French art?

SL: It is never moderate, but always powerful and extreme. I like that. Indeed, I cannot imagine art being any other way. I guess I am not very French in this respect.

HS: And in what respects are you very French?

SL: Linguistically, first and foremost, for French is my mother tongue. Otherwise I am French inasmuch as I reject certain things that are supposedly French. I am not pro-French and can’t even say I particularly like the French. In fact my dislike verges on hate. And this means, naturally, that it’s quite a struggle to accept even myself [laughs].

To be born of a woman condemned without fair trial, a woman condemned by the French government — that alone sufficed to spark my resistance, my personal crusade, for it caused me to be separated from my mother. At the same time, I am enormously indebted to my fate since without it, I would not be the Serge Lutens I am today — although that is perhaps no big deal, perhaps nothing but a flacon of purple perfume, there, on the table. But still … [laughs]!

HS: For the uninitiated it is indeed just a purple perfume.

SL: The word violet not only connotes the color but also contains a form of the French verb violer, meaning to rape or injure. And hence it also strongly suggests the transgression of borders. This is the French language with which I am so intensely familiar! I would not live in Morocco were French not spoken there.

“Women and I, we are one and the same.”

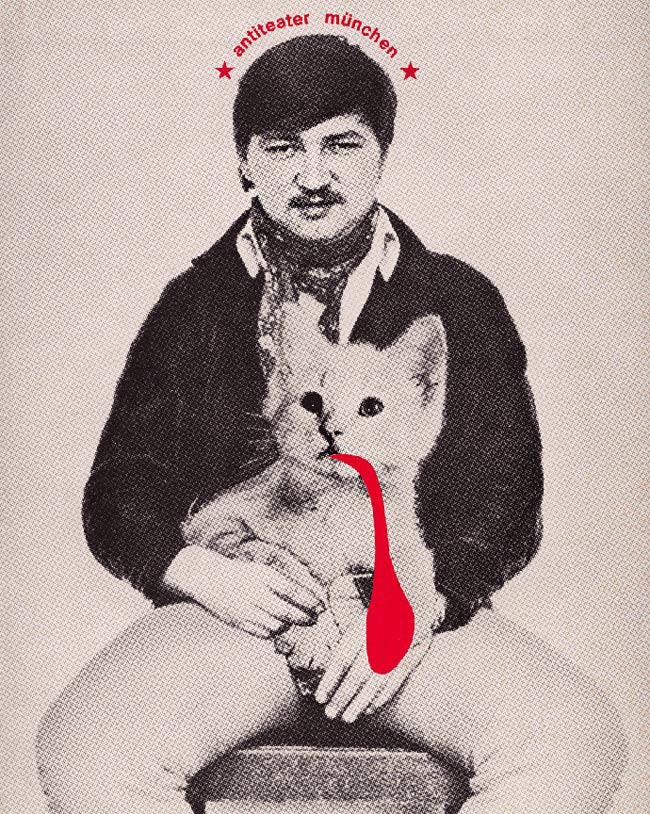

HS: I heard you are also a fan of Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s work?

SL: I hold Fassbinder in great esteem. He was a tremendous artist, by which I mean he sought constantly to express his own truths. A love of women, such as his, is rare among gay men — a certain distaste or even rage far more common. This man is very touching.

HS: I’ve always had the impression that he often bared his soul on screen through his female characters.

SL: Absolutely. Any man who shapes an image of a woman or womanhood simultaneously reveals his own character: as in, women and I, that’s me; we are one and the same. But ok: I will always be a boy nonetheless [laughs].

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1941 – 1982. Poster, Residenztheater München, 2012. Image courtesy www.residenztheater.de

Rainer Werner Fassbinder, 1941 – 1982. Poster, Residenztheater München, 2012. Image courtesy www.residenztheater.de

HS: Mind you, it’s said that Fassbinder didn’t always treat women very well in real life.

SL: He was probably enraged by his sexual inclinations. I see this happen often, even to men who are not homosexual yet who treat women badly all the same, because they simply cannot stand being in love with an unattainable woman. And they take out their frustration on women in general. And perhaps Fassbinder was somehow like that.

In the early 1980s I did a portrait of Ingrid Caven, a woman who worked a great deal with Fassbinder and even once married him. She talked about him a lot. I think he needed women. And the fact she married a homosexual? Well, perhaps she in turn needed just that kind of guy.

“Perfection is nothing other than death.”

HS: You spent lots of time in Japan when you were working with Shiseido and now you live mostly in Morocco — two extremely different cultures, or so it seems to me.

SL: I first spent time in Morocco in 1968, in Japan in 1971. Both countries have given me a lot and yet both were also a part of me before I ever travelled there, which is the reason I instantly fell in love with them. In Japan, all art is a striving for death, because perfection is nothing other than death. And death plays an important role in my life. Indeed, I could almost say that death is the great love of my life [laughs].

Beauty editorial art direction by Serge Lutens, 1972. Image courtesy of Serge Lutens.

Beauty editorial art direction by Serge Lutens, 1972. Image courtesy of Serge Lutens.

HS: And Morocco?

SL: Morocco is something else entirely. Art there is a song that weightlessly lifts from the lips and soars high. I find myself reflected in both those extremes.

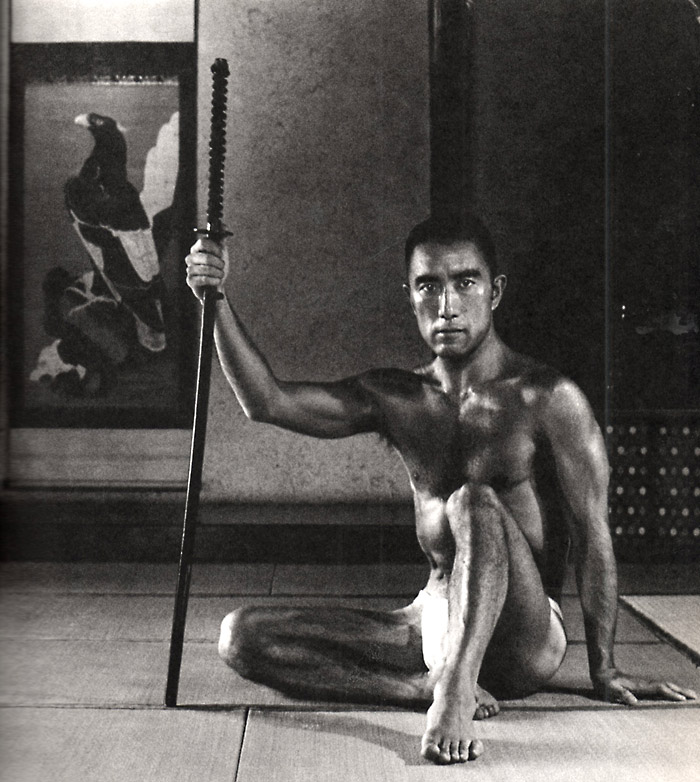

HS: Unlike we in the West, the Japanese do not strictly differentiate between art and artisanship.

SL: Everything there is one and appears to pursue the same principles. I attended a school of Ikebana there, where women learned the art of flower arrangement. It was considered nothing less than scandalous if merely a single bloom was ill placed. There are also incredible writers in Japan — Kawabata Yasunari, for instance — who follow strict rules to create consummate poetic images in only a sentence or two. And they always take things to extremes, at times to ridiculous extremes, as in the case of Yukio Mishima, a writer and political activist who in the 1960s recruited a pseudo-army in a bid to reinstate Imperial rule in Japan [and then after the failed coup d’état committed seppuka with his partner]. Yet his “army” and “coup d’état” were mere staffage: his goal was death. His ardent wish was to die for his Emperor. The Japanese have another regard for beauty, love and death.

HS: Calculated disorder and rupture both play a major role in Japanese art.

SL: In Japan there is an order even to disorder. And therefore actually no disorder exists — there is a distinct place and time for everything. Nothing can evade the greater order, not even death, not even suicide committed as a ritual act. This is absurd yet at the same time it is all too human.

“When one loves a thing deeply, one becomes that thing.”

HS: There has been remarkably little art-historical development in Japanese culture. The concern there is not so much innovation but perfectionism.

SL: The primary concern is to suspend time; the primary concern is death. In the 1980s I undertook an extensive trip around Japan and visited all the people who were listed as living national treasures. It was stupendous! I spent one or two, sometimes as many as three hours with each of these persons, mostly in silence. Among them numbered an old cabinet-maker who lived in a forest. He showed me a paperknife he had made, an identical one of which he had once given to President Carter as a gift.

Both of them had been carved from a single piece of wood with a knotty twist to it. It was from this twist or, one might say, from this paroxysm of the tree that the artisan had formed the paperknife’s handle, which was absolutely elegant and sublime. And when I looked at the man’s hands, I saw there this twist of the tree. His work with wood, his unerring sense of wood and its movement had turned the man himself to wood: he was a man of wood. It pleased me enormously to see that. When one loves a thing deeply, one becomes that thing. It is a form of metamorphosis.

Japanese poet and rebel Yukio Mishima, 1925 – 1970. Photo by Tamotsu Yatsò, 1970. Via: www.thule-italia.com.

Japanese poet and rebel Yukio Mishima, 1925 – 1970. Photo by Tamotsu Yatsò, 1970. Via: www.thule-italia.com.

HS: Not only does the artist form the material but also the material forms the artist?

SL: It’s a case of mutual adaptation. And that, I believe, is what I experience with women. It is not exactly homosexuality; I wouldn’t call it that. Rather, it’s a kind of sensitivity that enables one to gradually go over to the other side, so to speak, without even really noticing. This involves a risk too, of course, and may ultimately lead to problems.

I have spent a lot of time — well, my whole life actually — with women. And now I live alone. I venture to avoid all disasters, at least those of which I may be the cause [laughs].

“God is nothing. God is we ourselves!”

HS: That is very much in keeping with La Religieuse, since the nun too opts for a simpler kind of love. She devotes herself wholly to God.

SL: What a myriad of wonders this perfume holds! Probably no one will want to wear it after all I’ve told you [laughs].

But who or what is God? Does she or he have legs? Does he or she have balls? God for some women is female perhaps. Is she or he an illusion? Whatever the case, God is something we need. There are so many questions we are unable to answer. To whom should we put them, if not God? Certainly not to our presidents or other statesmen. They never have the answers. God is nothing. God is we ourselves!

I actually wanted to join a holy order myself, when I was a boy. There was a priest who looked after me at times and he believed I was destined to be a man of the cloth. He wore a ring set with a splendid amethyst the exact same color as this perfume here. He liked me to kiss his ring and he evidently felt very gay whenever I did so, for his hand would tremble. I was fascinated by that world.

In fact I admire this God-concept to this day. I know it is an illusion but I need God. Or rather, I need the illusion. And that is the reason I pray. I turn to God because, I have to turn somewhere: to thin air, to the ceiling, to this cup. God is this shoe, this cup — he is I and I am he. And yet he is nothing. He is all and nothing at one and the same time.

HS: Is the idea that our soul persists after death likewise an illusion?

SL: It is truly fascinating, this idea of the soul. Scientists today say there is something in man that survives his death. What exactly it is or in what it consists they cannot yet say. But the soul and life after death are now suddenly not only religious but also scientific issues. And science is certainly very soothing to the human soul, for it offers us certitudes — in this particular case a dreadful certitude. For I find it horrific to think something of me will persist after my death. What on earth am I supposed to make of this certitude?

HS: Thank you, Monsieur Lutens!

ABOUT SERGE LUTENS

Name: Serge Lutens

Occupation: Artist, Founder, Creative Director

Location: Paris, Marrakech

Info: www.sergelutens.com