My first trip to Barcelona — yet the Sagrada Familia and Olympic Village warrant barely a passing thought as I make my way straight to the HQ of Ramón Monegal, a perfumer whose work is highly rated by those in the know, and whose life has never been short of surprising twists and turns. He is the reason I am here. www.ramonmonegal.com

This feature is a proud finalist of the 2017 Perfumed Plume Awards.

It’s a family affair.

Born of a major perfume dynasty that under the Myrurgia logo enchanted not only the Spanish court but also the rest of the world for a good four generations, Ramón initially studied architecture before joining the family firm as a perfumer in 1978. In the 80s Myrurgia began to expand its portfolio, acquiring licenses and brands such as Adolfo Dominguez, Inès de la Fressange, and Etienne Aigner, to name but a few. But Myrurgia was swallowed up in the year 2000 by perfume giant Puig, creator and distributor of scents for such illustrious brands as Prada, Paco Rabanne, or Penhaligon’s — and, admittedly, also for Shakira and Barbie.

Ramón’s remit was to manage all of the brands and licenses Puig had bought from Myrurgia — the chance of a lifetime! Yet after only seven years Ramón decided to leave the company, where there was too little room for his own ideas and vision. As a sort of catharsis he penned La Perfumista, a novel in which a successful architect leaves her past behind to launch a new career in the world of scent … Any similarity with persons alive or dead is in this case neither purely coincidental nor unintended! In 2009, finally, he decided to perpetuate the family tradition under his own name.

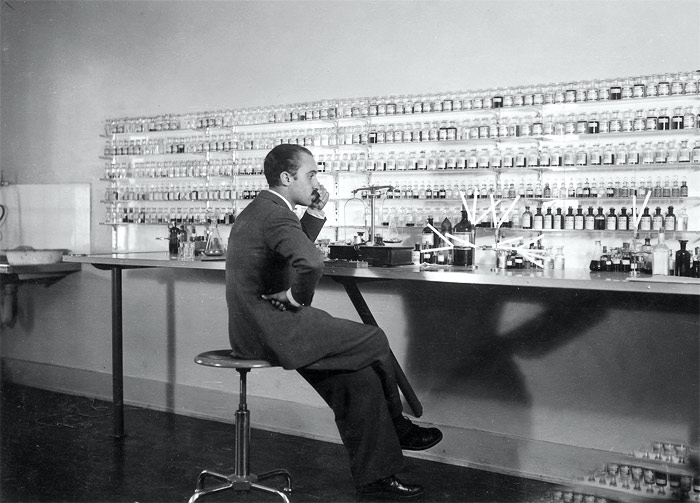

Ramón’s father Esteve Monegal Bofill in his laboratory. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Ramón’s father Esteve Monegal Bofill in his laboratory. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

I’m a little early, to be honest, when I step into the Ramón Monegal showroom on the bustling commercial strip Carrer de Calvet, but at least this gives me ample opportunity to look around in peace. Ensconced in low light I find dark timbers, embossed gilt wallpapers, and ceiling-high shelving, which to my mind speak not so much of a flagship store as of the intimacy of a connoisseur’s library.

Then Ramón Monegal enters the showroom, accompanied by Laura, his daughter. Later, I get to meet the rest of the fifth generation posse, namely Oscar and Hector, Laura’s brothers: all three already involved in the family business. The maestro — casually dressed in black, and with minimalist wire-rimmed spectacles on his nose — is suited to this environment to a t. Which is hardly surprising given that the interior design of the space is entirely his own. He gives me a warm welcome and leads me to the seating at the rear of the showroom, past shelves on which the Monegal scent collections are neatly lined up in flacons that have a hinged Bakelite lid doubtless inspired by old inkwells.

Ramón Monegal with Laura and Oscar. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Ramón Monegal with Laura and Oscar. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Writing with perfume.

A showroom that feels like a library, a perfumer who writes novels, and scents in inkwells: Do I sense a pattern here? “I’ve come to the conclusion that perfume is a language with which to communicate values and stories and so, for me, it really does make sense to compare perfume to literature,” Ramón Monegal confirms. My intuition appears to be on the right track: this place really is a library of olfactive literature and the man in front of me really is an author who writes with fragrance instead of with ink. “I too was trained in the vocabulary of music — notes, accords, and compositions — but experience made me wiser,” he continues. “Today, I prefer to speak of words and sentences. After all, there are countless words in this world but only seven notes in a scale.”

So, if perfume compares to literature, is Ramón Monegal a writer of prose, novels, or poems? “There’s a story in every perfume, because each has a history, each is a succession of smells that emerge and blend, just as a novel unfolds from page to page. Nevertheless, a perfume to my mind is more a poem than a novel: there are fewer words yet each and every one of them is there because it’s essential. Like a poet, the perfumer is constantly analyzing a composition, cleaning, refining, and substituting components. There is nothing unnecessary in a good fragrance, just as there are no fillers in a poem.”

Ramón Monegal: “Most olfactive values are predefined by nature.”

How exactly does Ramón Monegal conceive his olfactive poetry? “When I create a perfume I don’t pick ingredients at random but on account of their meaning,” he clarifies. “Each ingredient represents an individual value. Hence, if you know what you want to say with a fragrance and which values you would like to convey, you know too which essences to chose. And though you can create countless different formulas from this one selection, intuition tells you clearly which one is right for which particular occasion.”

But from where do these qualities and values derive? Are they determined by nature? Or are they cultural attributes? “Most values are predefined by nature. Wood, for instance, is associated with masculine qualities such as security and flexibility, on account of its original function,” explains Ramón by way of example. “When I work with wood, I work with these values. Flowers have a scent in order to seduce and attract insects for pollination. That is a clear function, a value inherited from nature. And, incidentally, there are as many ways to seduce as there are flowers: the rose symbolizes love, jasmine sex, lily of the valley romance … These qualities are not necessarily linked to gender, so anyone can make them their own. Men too like to seduce.”

Pharao offering an incense pot (ostracon) to the Gods. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

Pharao offering an incense pot (ostracon) to the Gods. Photo: Wikimedia Commons.

All perfumes should seduce.

So, deep down in our hearts we’re hoping to seduce someone, whenever we put on some perfume, I wonder aloud. “All perfumes should seduce us in one way or another, Ramón replies. “After all, the purpose of fragrance, initially, was to seduce the gods.” Then he launches into a brief anthropological digression: “The ancient shamans burned incense and other substances to connect to the divine sphere — and also to manipulate other humans by creating olfactory images of power: the smell of power. We all know how to control our visual appearance: our hair, accessories, and dress. Also we each have a gestural image, as well as an auditory image expressed through the timbre of the voice. And then there is our smell. We invented perfumes so as to develop an olfactive image.”

But considering the abundance of possibilities to tweak one’s olfactive image in this store alone, I ask how we can ever be sure of choosing the right perfume for ourselves? “In my experience, most of the people who come in here don’t know how to express themselves, and that makes them insecure,” replies Ramón. “These clients know what they want. They need assistance and they deserve to be educated. They need to learn by which criteria to evaluate a fragrance, just as they would with a wine. To say ‘I like it’ or ‘I don’t like it’ is not enough.”

Vintage Myrurgia flacon. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Vintage Myrurgia flacon. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Ramón Monegal: “Children are very good at differentiating smells.”

What can be done to empower consumers, to enable them to make an informed decision? “Every time I explain my philosophy to a client, the client makes the perfume his own. This is my greatest satisfaction,” Ramón confesses. Then: “Children too are very good and very fast at recognizing and differentiating smells. It would be a huge cultural leap if one could educate them about fragrance at an early age, for they learn so much more easily then.”

It’s pretty safe to assume, given this family background, that Ramón Monegal had the benefit of an early education in all things olfactive, or possibly even that some molecular fragrance sequence has long since become embedded in the Monegals’ DNA. How did he feel about growing up in a perfume dynasty? “In my family it was completely normal to discuss fragrance. The topic was present for as long as I can remember. My father was a perfumer but a great chef too. We probably spoke as much about scents going down one’s throat as about scents experienced through one’s nose,” he laughs.

Growing up in a perfume world.

Was his pursuit of the family tradition predestined from an early age? Was he expected to follow as a perfumer in his family’s footsteps? “There was no pressure. I wanted to be an architect and actually did study architecture. But during my summer break I went to Geneva and ended up working with Artur Jordi Pey, the master perfumer at Firmenich. It was this which led me to abandon architecture in favor of perfumery.” Ramón Monegal trained in Grasse and Paris besides Geneva — And what secrets of perfumery did he learn from his father in Barcelona? Ramón reflects for a moment before he answers: “My father didn’t teach me. I don’t know why. He was a perfumer, but not a master. A master, to my mind, has a vocation to teach, and my father didn’t.”

What about his own palpable passion to teach, to impart knowledge? Does he see himself as a mentor? “I didn’t realize this until I studied my ancestors. My great-grandfather — who traded in essential oils and perfumes, and founded the family business — wasn’t only a talented merchant but a qualified teacher too. He founded two public schools in Barcelona. And his grandfather was a visual artist, but also had a teacher’s vocation.”

La Pedrera building by Antoni Gaudí. Photo: Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons.

La Pedrera building by Antoni Gaudí. Photo: Bernard Gagnon, Wikimedia Commons.

Returning to the topic of Ramón’s early life, I ask about his earliest olfactive memory. “When I was a child we spent summers in our country house on the coast. An old man there used to heat wood over a fire so as to be able to form it and build a boat and when he was done he’d weatherproof it with hot tar. I remember the magic this transformation held for me as a child — and I remember the smell that went with it. One other thing I recall: we lived across the street from Gaudi’s La Pedrera with its phantasmagorical chimneys. The form of the smoke they emitted constantly changed and so too did its aroma — or at least that is what I imagined. At night the chimneys looked to me like ancient warriors, guardians of perfume. That’s what true perfumers are: guardians of perfume.”

The true guardians of perfume.

Who are the enemies that perfume needs to be guarded from? “First of all we need to protect it from marketing,” Ramón begins. “The big luxury brands have made a mistake. They’ve turned perfume into a huge business — far too big a business — and appear to have forgotten that clients want a unique experience. Clients no longer have access to the creative perfumer yet he alone is in a position to explain his work, explain his philosophy. Until the 1920s, perfumers had their own stores so there was nothing extraordinary about being able to meet them. But then fashion brands usurped their role. Marketing won the upper hand, advertising flourished, and billions were invested — but ultimately, consumers understood less about perfume than ever before.”

“The least you can do, when speaking of a perfume, is to name the person who created it,” Ramón declares. “Scent is one of the rare instances where the author does not sign the artwork. And the industry has always colluded in keeping perfumers hidden. It should be obligatory to name them, just as in music or literature.” The number of classically trained perfumers on the planet is small, no more than around three hundred and sixty. One might think such rare birds are much sought after and have some clout. Why have they never stood up together for more recognition? “The thing is, perfumers are very well paid by the companies they work for. So most of them won’t ever complain. What we need is for all perfumers to come together to claim their rights.” A trade union for perfumers? “Exactly,” Ramón replies, much enthused: “a worldwide perfumer’s union.”

A renaissance of artisanal perfumery.

Experts estimate that more than 2 000 niche brands exist today, and their number is growing. Is this just hype born of the fact that big brands are finding it increasingly difficult to forge bonds with consumers? “The dream of every client is to wear a perfume that is designed especially for him or her,” Ramón assures me. “Yet the majority of luxury brands are geared to the mass market these days, and sell millions of units. It’s hard to feel unique when millions of other people smell just like you.

Now, however, thanks to the Internet, people are discovering small and often unknown brands that produce scents they’ve never heard of before. These may be even more expensive than the scents from luxury brands — but then again, they offer a degree of exclusivity that one otherwise finds only in customized fragrances. And despite them lacking Chanel credibility, so to speak, and despite the elevated price, these products sell well online. If it wasn’t for the web, they would never have stood a chance.”

Endangered olfactive species: Oak moss. Photo: Shutterstock.

Endangered olfactive species: Oak moss. Photo: Shutterstock.

Ramón Monegal: “The perfume industry needs to build a strong lobby.”

When I ask which other menaces to perfumery are lurking, Ramón pronounces a single acronym, the very sound of which is enough to make any perfumer alive recoil in horror: “IFRA! The International Fragrance Association is attacking the use of natural ingredients. Take cinnamon: there’s no restriction on its use in food, but in perfume, certainly. Another example is Balsam of Peru, a permissible ingredient in ointments for open wounds, although it then enters the bloodstream, but forbidden for use in perfumes. They explain this mainly with allergies but look at the facts: 40 % of all fatalities ensuing from allergies are caused by pharmaceuticals. The second leading cause is food, the third, bee stings. Perfume: not a single case to date.”

There’s no denying that the fragrance sector is sick and tired of Brussels’ never-ending stream of regulations. Critics are afraid that perfume culture as a whole could suffer serious damage, and indeed certain classic fragrances are already merely a shadow of their original selves, because vital ingredients such as oakmoss or styrax gum have been outlawed. “The food and pharmaceutical industries know how to protect themselves, whereas perfume industry players too often act not as allies but as enemies,” Ramón elaborates. “They didn’t wake up until IFRA started moving in on rose and jasmine. Then Chanel raised its voice and said: ‘No way!’ The perfume industry needs to build a strong lobby in order to protect itself from this kind of aggression.”

Fiesta: Celebrating one hundred years of fragrance history.

Energetic, impassioned, and ready to defend his terrain — no wonder that a free spirit like Ramón Monegal likes to be his own master rather than bow to some company’s PC dictates. It is thanks to his creativity and love of liberty that the Monegal family is able to celebrate one hundred years of perfume history this year, with a richly illustrated centenary album conceived and edited by Ramón, and an aptly named jubilee scent, <i>Fiesta</i>. The scent comes in a lavish packaging in the shape of a book — what else?! — in an edition comprised of 2 016 individually numbered pieces. “It’s not the special packaging that is limited, as is usually the case, but the fragrance. There won’t ever be another batch — unless, that is, someone comes to Barcelona to beg for it in person” Ramón adds with a wink.

Limited centennial edition of Fiesta. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

Limited centennial edition of Fiesta. Photo courtesy Ramón Monegal.

For Ramón, the scent is a way of paying homage to his homeland, Spain: “It is clearly distinct from the Parisian tradition. In literature the Iberian Peninsula is called ‘bull’s skin’ because of its shape. That’s why there’s leather in this. Then there is linden blossom, a scent that is very present in Barcelona in early summer; and I added the smell of fireworks — because that’s what you want for a real Fiesta. Plus we added to the formula a very rare and special ingredient: oil from the olive tree flower, sourced from a tiny Andalusian manufacture.”

Is there such a thing as a particularly Spanish perfume tradition? Ramón is absolutely positive about this: “Incontrovertibly! Eight centuries of Arab domination have left their mark. Arabs cultivated orange trees, created fragrant gardens, introduced exotic spices. They also invented alcohol as well as the techniques of distillation and of extracting fragrance from flowers. Were it not for these three skills, perfumery would not exist. In Spain, olfactive culture is very important; perfume accompanies you your whole life long. There is perfume for children, for young people, for grown-ups. Spanish children are perfumed from the day they are born; older men comb perfume into their hair until the day they die.”

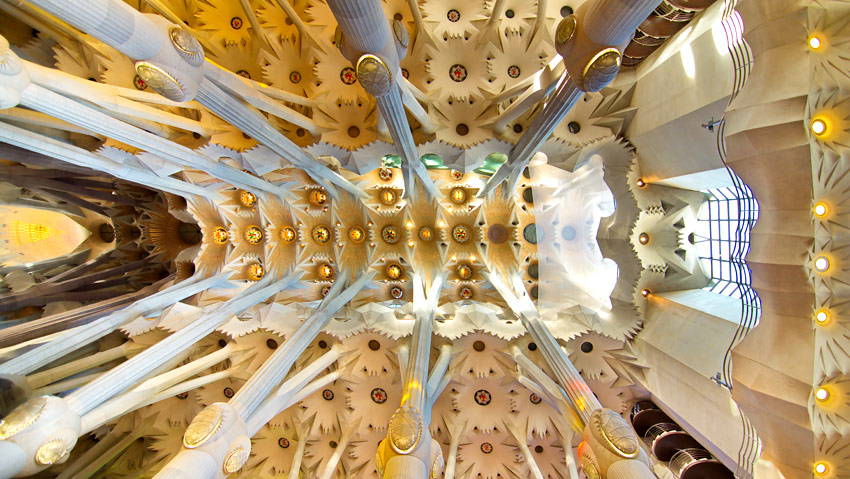

The vault of Sagrada Familia. Photo: Shutterstock.

The vault of Sagrada Familia. Photo: Shutterstock.

The wondrous laws of nature.

As we continue to flip through the centenary album Ramón explains to me his choice of texts and images: portraits of the founders of Myrurgia, flacons and packaging designs from the early years, macro-photography of herbs and other ingredients. Instinctively, I linger over a double-page spread: on the left, the astounding vaulted central nave of the Sagrada Familia, a seemingly effortless fusion of symmetry and ecstasy; and on the right, a view of the filigree ribbed vault of Calatrava’s Oculus in New York’s WTC Transportation Hub: two Iberian architects who successfully applied the wondrous laws of nature to the work of human hands; two architectural monuments that trace an arc from early-twentieth-century Modernismo to the present day.

The reason Roman Monegal concluded his declaration of love for a century-old passion for perfume with these images speaks for itself: they are an expression of his hope that the legacy will be not just preserved but also perpetuated — by the House of Monegal in its fifth generation as well as by all the rest of the world’s fools for fragrance and suckers for scent.

¡suerte, maestro!

ABOUT RAMÓN MONEGAL

Name: Ramon Monegal

Occupation: Perfumer

Location: Barcelona

Info: www.ramonmonegal.com