Though Geza Schön tries to avoid the limelight, he is one of the best known perfumers in the field of niche fragrances, and also a highly successful scent creator when it comes to sales and creative impact. Ten years after his radically effective Molecule 01 changed the perfume industry’s landscape, Schön brings us the newest extension to the line, Molecule 04 and Escentric Molecules 04. We met up with the arbiter of scent at his penthouse in Berlin to learn as much as we could about his visionary processes.

PORTRAITS & STILLS: Franziska Taffelt

“The market is saturated with scents.”

Helder Suffenplan: You recently released your new scents, Molecule 04 and Escentric Molecules 04 — exactly ten years after the launch of Molecule 01, which is meanwhile a modern classic. The niche segment back then was still tiny whereas these days it seems there’s a new brand out daily. Why is that?

Geza Schön: It’s much easier now to launch a scent. To say nothing of the chutzpah of certain people who recycle completely tired, boring concepts or revamp old brands without a qualm. There are a huge number of really cheesy scents around, in my view, and I find myself thinking: Oh fuck! And I feel sorry for the people behind them too, since they’re likely to be a bit of a flop. The market is already saturated with scents — there’s really no reason for us to put up with any more of them, especially if they don’t justify their existence.

HS: Which factors make it easier to launch a scent these days?

GS: Well, the Internet for one, with its endless opportunities. You can sit at home and order more or less everything you need to create a perfume. It’s also become easier to approach perfumers. And there are even companies around now that’ll sell you off-the-shelf perfumes that you can then market yourself, under your own label. Besides, you don’t need to be filthy rich to finance a batch of, say, between one and five thousand bottles.

Berlin skies. Portrait of Geza Schön by Franziska Taffelt.

Berlin skies. Portrait of Geza Schön by Franziska Taffelt.

“No scent from the last decade made me say: ‘Wow’!”

HS How have the scent creations themselves changed?

GS: Strictly speaking, not a lot has happened over the last ten years. Of course, the broader the range, the harder it is to break away and come up with something totally new that will grab people’s attention. It used to be that almost every scent had something exciting going for it, and a statement to make. Also, it was possible back then to work on a perfume for longer, to really refine it and turn it into something special.

It was a time when a lot of innovative products came along, both synthetics and exotic natural varieties. But I can’t think of a single scent from the last decade that has made me say: “Wow! They’re onto something there.” That’s a pity. Today, everyone’s swimming in the same old soup — especially when it comes to mainstream women’s perfumes. It’s insane, how no one in that sector is prepared to take a risk.

Where it happens: Geza Schön’s laboratory in Berlin. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

Where it happens: Geza Schön’s laboratory in Berlin. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

HS: Why do you think that is?

GS: These scents need to be 100 % up your nose the moment you spray some on when rushing through the duty-free shop. And they need to smell somehow familiar, which is why the manufacturers return time after time to past successes. They count on people being drawn to things they have smelled before.

HS: In creative sectors such as music and film the democratization process set in around ten or twenty years ago: people used to need a studio to make a record but these days they can sit around the kitchen table and create a smash hit. Of course there’s a lot of rubbish around, but also plenty of good stuff that would never have seen the light of day in a studio system. Do you think it’s possible for people without a classical perfumer training to create novel, exciting scents?

GS: If you train with Firmenich or Symrise or IFF — the top-notch companies that necessarily know what’s happening on the ground — then you pick up a bunch of paradigms that may very possibly blinker you. Whereas the greenhorn who gets into the business literally just by following his nose is spared that. Admittedly, the successes and fab solutions any self-taught perfumer comes up with are likely to be strokes of luck. To make a lateral entry as a newcomer in this profession, and get ahead, is probably as hard as it gets.

“Perfume is the science of interplay.”

HS: Because of its extreme technical complexity?

GS: Exactly. Perfume is the science of interplay, the interplay of natural and synthetic bases and ingredients in light of a certain sense of harmony — you have to grasp that much to even begin. And then spend years examining it in order to gain a sense of: “I get it now” or “I’m starting to get it.” Because these ingredients in all possible quantities, in all possible proportions, in all possible permutations behave after all according to principles that you get better at year by year, or decade by decade. Simply because you’ve meanwhile made a bazillion more experiments, in order to see whether what you imagine can actually work.

HS: As in, you have to know the rules to break the rules?

GS: I’d sign off on that statement, any day. Because what I’m after, ultimately, is a product that corresponds to my creative vision and yet also functions in technical terms. Like: the ingredients have to meet standards laid down by law; the dosage shouldn’t be too high but still enough to guarantee a blooming, a bonding, and a harmonious development — or a disharmonious development, if that’s what I choose to create. But I would never have that conscious choice, that level of control, if all the ingredients were new to me. Just as I could never hope to be picked for the second league if I’d only just started playing football. It simply wouldn’t add up.

“The sense of smell is so hard to pin down.”

HS: Do you consciously keep an eye on that scene?

GS: No, not really. Then again, not much escapes me either — for instance, when I’m at the Exsence, [annual niche perfume trade fair held in Milan], where I see some of these brands and get to meet the people behind them. I think any other creative sector you care to name can measure quality and aesthetics more objectively than the perfume business can. It’s such a very difficult discipline. People often feel insecure when they sniff a scent, because they don’t have the vocab to describe it. Nor much of a clue as to how it all works.

When it comes to hearing or touching things, we are much better off. And visually too, of course, since that is the sense that drives us. But the sense of smell is so hard to pin down, so arbitrary. There’s a survey IKEA did that says fifty percent of 16 to 30-year-olds would rather give up their sense of smell than their smartphone: not five or ten percent, mind, but fifty! So not just the odd idiot or two, but half of today’s young adults say: “Hey, fuck, no, I can’t live without it: I’d rather cut off my nose.” Though I bet they overlook that you can’t taste a thing if you have no sense of smell.

“The crux is to create something that makes people feel good.”

HS: A lot of people in the business want to see perfumes accorded the status of art, on an equal footing with painting, music, or sculpture. There’s talk of l’art du parfum, or perfume as art. I find that problematic since a criterion of art, in my view, is the capacity to be disruptive, to be seriously challenging, and to shift borders. And to what extent can perfume afford all that if at the end of the day it’s meant to sit on a shelf and wait to be purchased? Should we even want it to afford all that?

GS: The crux is to create something that makes people feel good, even if it tests their limits. But there are some scents around that take things a little too far. Then I say to myself: “Hang on; you want people to fall in love with your perfume and buy it, right? So why then does it smell so revolting?” Of course you fall in love with a name, or a concept, or even the shape of a bottle, right, but first and foremost with the elixir. After all, you’re prepared to part with one or two hundred dollars for the pleasure …

Besides which, there is nothing easier than shocking people: to make a performance of a perfume, to really get up people’s noses with some crass and lasting bonding or other is no problem. But who’d ever want to wear it? And that’s why I find it ridiculous the way certain brands overstate their case.

“The need to shock is so puerile.”

HS: That for me is the crucial distinction between high art and applied arts such as fashion and perfume: to admire a Picasso on the wall or to look like a Picasso oneself are two very different things.

GS: I completely agree. Moreover, we can distance ourselves from whatever we see just by shifting our gaze. But when a perfume gets up your nose there’s no escaping it. It’s all around you and also in you — you breathe it in, it quite literally takes possession of you; and if it’s bad then that’s really bad.

HS: Of course there are artists who use scent as a medium to alter perceptions of a space for example, which can be a truly awesome physical experience — but only in the right context. They’re not stuff you’d dab on before heading out to dinner.

GS: Absolutely. Perfume and art do intersect or overlap at certain points, but that’s all. Ideally, we perfumers still aim to conjure a sensuous and satisfying sensation, not to make people’s blood run cold — although horror films admittedly have their fans. But hey, I personally don’t see the sense in using a sledgehammer to crack a nut. Subtlety still is of interest, not least in the visual arts, in my view. I’m no fan of people like the Chapman Brothers, or Tracey Emin, or that idiot with the formalin, what’s his name again?

HS: Damien Hirst.

GS: Yes, Damien Hirst. Shock art. The need to shock is so puerile. Okay, it’s established stuff, they made a mint, and can do what they like. But I find it inane. There’s art that uses more subtle methods and still puts a message across. And I think if you can do a thing in a peaceful way and people understand and enjoy it then it’s the best way to go: more challenging, for sure, but also much more elegant.

“I love animalist notes — but without counterbalance the whole thing smells like poop.”

Vintage ad for Kouros by Yves Saint Laurent. Image: original scan by the author.

Vintage ad for Kouros by Yves Saint Laurent. Image: original scan by the author.

HS: How do you explain the fact that animalics — the use of animalist notes — is suddenly all the rage?

GS: Is it?

HS: So it seems to me at least, over the last two years. How far can one go with that, without getting thrown off a plane?

GS: Well, I love animalist notes and always have. They’re what made waves in the 80s, with Jaques Bogart’s Furyo or Yves Saint Laurent’s Kouros. There were real stinkers: ten or twelve percent animalis [a base made by the flavors and fragrance manufacturer Synarome], which is pretty fascinating, for starters. And sure, I also like castoreum, civet, ambergris, and musk … Lots of stuff is sadly no longer available in its original form. But the bottom line here too is: people have to love it. Animalist notes are fine but you have to create a counterbalance or the whole thing ends up smelling like poop.

“For me, it’s about keeping an open mind.”

“Exhibition 0,10” with Kasimir Malevitch’s Black Square, Petrograd 1915. Via: www.wikipedia.com.

“Exhibition 0,10” with Kasimir Malevitch’s Black Square, Petrograd 1915. Via: www.wikipedia.com.

HS: With Molecule 01 you too broke the rules, or at least a lot of people saw it that way. I must tell you this anecdote. I was seated at a dinner next to a respected perfumer and the name Geza Schön came up. She got very worked up, claiming what you did with Molecule 01 had been a stab in the back of anyone who buys perfumes and especially of anyone who makes them, because it contains only a single ingredient, Iso E Super.

I replied that, quite apart from the fact that lots of people love that scent, wear it gladly, and buy it of their own free will, Molecule 01 is a bit like Malevich’s “Black Square.” And that of course anyone can paint a black square but in 1915 no one but Malevich was able to think a square in such abstract terms. At which point she said, she detests Malevich …

GS: She said that?

HS: She did. What does it do to you, to hear that Molecules 01 can still trigger such a reaction, ten years after its launch? Does it bother you or do you take it as a compliment?

GS: Neither. It just goes to show how narrow-minded also perfumers can be. If a chef managed to bring people to their knees with a dish containing a single ingredient, no one would accuse him of perfidy. For me, it’s about keeping an open mind. Are you interested in new things, and willing to learn? Or do you eat the same thing every day and always take the same route to work? Are you hungry and foolish now, or not? Sometimes you have to force yourself to break out of your comfort zone and risk a paradigm shift.

“Iso E Super is a weapon!”

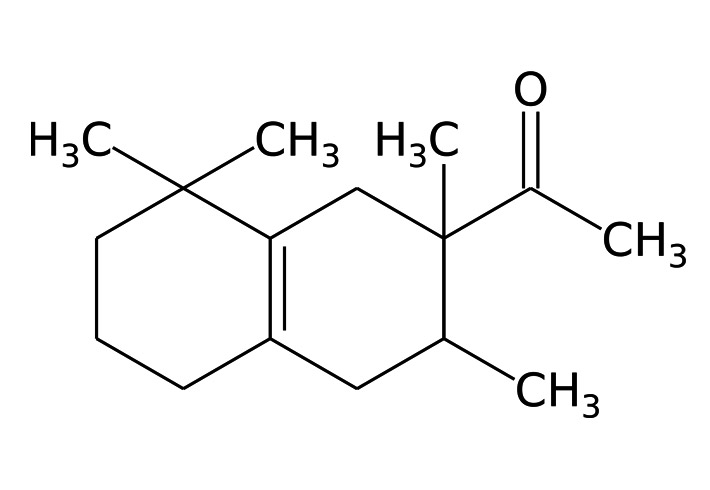

A very special molecule: the structure of scent Iso E Super.

A very special molecule: the structure of scent Iso E Super.

HS: How and when did Iso E Super first catch your eye — or rather: your nose?

GS: I started out in 1990 at Haarmann & Reimer, smelled this raw material there, and instantly thought: Fuck me! I quickly realized that most of the perfumes I found fascinating contained Iso E Super. So I simply got hold of some and used it in isolation. That story with my friend Michael is true, unfortunately. We were in the Fes [bar] in Kassel, he was using Iso E — a drop here, a drop there — and five minutes later a woman came over and asked: “What is it here smells so damn hot?”

So I had a chat with her and it turned out she was into Fahrenheit and Trésor too. Fahrenheit has twenty-five percent Iso E, Trésor twenty percent. Those two perfumes couldn’t be more different, but since they both contain tons of Iso E, it was logical … And this opened my eyes to what a weapon it is. Nothing more than that, initially; but then in 1994 I tried to interest the Diesel people in it.

HS: So many years before you finally launched it yourself?

GS: I kept it to myself at the time because I wasn’t interested in launching some molecule or other but in learning about perfume and creating fabulous scents. In 1994 Diesel was planning its first perfume and consulted Haarmann & Reimer. The Diesel account at the time was with Alessandro Gualtieri.

HS: THE Alessandro Gualtieri, founder of Nasomatto and Orto Parisi?

GS: The man himself. I can still see myself standing with him outside our hotel one evening and saying: “Ok, we’ve now shown them around one thousand perfumes and they still don’t have a clue what they want. Show them Iso E Super.” And he said: “No, we can’t do that. That’s too crazy even for Diesel.” He couldn’t do it, even though he has a brilliant mind, an unconventional mind, to boot. It was too early. The paradigm in his brain was: We sell perfumes, not molecules. So I put my idea back in the drawer again.

HS: Were you disappointed?

GS: I was even a little pissed, to be honest. But now I fall to my knees each day and offer up a prayer of thanks to Alessandro.

“I’d never have thought Molecule 01 would take off on this scale.”

A milestone in perfumery: Molecule 01 by Geza Schön, 2016.

A milestone in perfumery: Molecule 01 by Geza Schön, 2016.

HS: I can believe that, seeing how successful the Molecules series is. Lots of people really love it. At the same time, everyone who wears it has the feeling it’s an insider tip. How does that gel? Is it a case of good marketing and sustained sales? Supplying it to [the German major drugstore chain] Douglas surely must be quite tempting — except that would kill it within two years.

GS: We’d never do that. No way. There’s no question of that at all. We want to keep it as a niche product but of course also sell it worldwide, because it does function, actually, in every part of the globe. Thanks to the research genius Hanns Hatt of the University of Bochum we know that Iso E Super — unlike almost every other raw material — really does appeal to our vomeronasal organ on account of its molecular structure. The effect is such that we not only perceive it as pleasant but are physically, magnetically drawn to it. And I’m not speaking metaphorically. People run after you on the street and ask: “Hey, excuse me, but what is that scent you’re wearing?”

Geza Schön in his lab. Portrait by Franziska Taffelt.

Geza Schön in his lab. Portrait by Franziska Taffelt.

HS: In the interviews we do for Scentury, Molecule 01 ranks among the most often cited brands when we ask what people are wearing today or whether they’ve a perfume story to share. One of the interviewees who mentioned it, is jewellery designer Akke Aimaq. I used to think it was just an urban legend or that you’d simply done a great job of PR. But I’ve meanwhile heard so many people say they smelled it first on a stranger and felt compelled to ask what it was that I do now really believe it.

GS: It is pretty weird. I’d never have thought it would take off on this scale. And yes, those who wear it think of it as “their” perfume. There is something singular about it. And simple too. I really don’t know how to explain it and it still surprises me, time after time. I mean, even I smell it on the street sometimes and find myself thinking: “What’s that? It smells fantastic.” I’m literally overcome first by the physical components and only then does my brain come into play.

HS: A lot of other brands are now turning the spotlight on synthetic molecules — Æther, Zarko Perfumes, or Nomenclature, to name but a few. How does that make you feel?

GS: I don’t see myself as a trendsetter or so. It was clear that the focus on natural sources would shift at some point. The pyramids always used to say: bergamot, mandarin, citrus, basil, etc. as if a perfume were full of natural goodness. Yet ninety-five percent of the formulas were synthetics from the start. So it’s only logical that synthetic molecules are now being discovered and branded as an asset.

Molecule 04: “With Javanol, things are jumping.”

Molecule 04 and Eccentric Molecules 04. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

Molecule 04 and Eccentric Molecules 04. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

HS: And now here come Molecule 04 and Escentric Molecules 04. Which both revolve around the sandalwood molecule, Javanol. Are there many other molecules as special and effective as Iso E Super and Javanol, or will the series at some point come to an end?

GS: No, there aren’t many. Iso E Super has a unique status because it is so incredibly complex, smells good, has excellent bonding, and a good sillage —basically, all one could ever want from a synthetic fragrance. Most other scent molecules work only in combination, however, so the series will run dry one day indeed. There’ll certainly be another five, I think, and then we will see.

HS: What’s so special about Javanol?

GS: Javanol has been around for a good fifteen years. It’s perceptible even in the tiniest doses and enhances both bonding and sillage. Not a cheap material, by any means, though thankfully the price has now dropped a little. Most comparable materials are much more monotonous and linear, with a lot less going on, in short. Whereas with Javanol, things are jumping: it has something silvery, metallic, but with an upper note of grapefruit peel, and a rose note that hits you only later — plus of course the sandalwood components.

HS: All that in a single molecule?

GS: Absolutely, that’s what makes Javanol so amazing. I am very happy with this choice. We have already had positive feedback. Of course it’s a risk this time too. People will have to realize that Javanol’s not going to hit you with every intake of breath — and that is how it should be. It shouldn’t be getting up your nose all the time. You wear it, you smell good, but it leaves you in peace. Personally, I find the idea of a perfume that wraps me in a scent cloud rather alarming.

HS: Lots of brands emphasize the sillage more than anything, i.e. the physical range and intensity of your products.

GS: But I ask myself: “Is that what people really want?” If you use Égoïst you smell it all day long, with every breath, through each nostril, non-stop. Isn’t that a little anachronistic, to wear a perfume that gets on people’s tits all day?

“I’m into originals and original ideas.”

Project Renegades: Mark Buxton, Geza Schön, Bertrand Duchaufour. Photo: courtesy of www.willbeabrand.com.

Project Renegades: Mark Buxton, Geza Schön, Bertrand Duchaufour. Photo: courtesy of www.willbeabrand.com.

HS: You’ve created several lines over the years: the Project Renegades in cooperation with Bertrand Duchaufour and Mark Buxton, for instance; and the two series Molecules and Beautiful Mind. What made you decide not to build a uniform “Geza Schön” brand?

GS: I don’t enjoy the limelight. I’m into originals and original ideas. The Beautiful Mind series has set itself the goal of featuring women with extraordinary intellectual or physical capacities.

HS: What put you on that track?

GS: One might say Paris Hilton put me up to it. I wanted to show that you don’t need to be a big-bosomed celebrity or a rich kid to be a perfumer’s muse. The first perfume was about Christiane Stenger and her astounding capacity to absorb and retain information, a capacity she developed on her own, independently and playfully.

And Polina Seminova is probably the best ballerina in the world. Very different women, but both of them prove that to do a thing you simply need to make a start. And doing, in the sense of “get up and go for it,” is vital to a woman’s identity, in my book. Just being a chick out shopping for a Louis Vuitton handbag, putting on the lipstick, and pouting: “Look at me” is not good enough. The world reduces women to their sexual attributes and seriously discriminates against them in lots of ways.

HS: The reasoning behind my last question on brand strategy is that it would be much simpler to sell a brand with the name “Geza Schön Fragrances” to Estée Lauder or L’Oréal. Which is a goal lots of perfumers dream about.

GS: I couldn’t give a fucking shit. Money for me is no incentive — no way. We don’t speculate like that. We want to make things that don’t yet exist, do things that haven’t been done, but not because we’ve certain strategies in mind. The same goes for Paul White, our art director. If a project allows us to do everything again, but differently, I’ll check that box — but only then. For sure, I also make perfumes for individuals or brands, if they pay me to; I don’t rule that out.

HS: Your father was an art teacher. and when you were talking about the Beautiful Mind series just now, Beuys’s concept of the social sculpture sprang to mind …

GS: Joseph Beuys, Francis Bacon, Roy Lichtenstein, those are the heroes of my youth! Yes, I grew up immersed in this art context. I mean I’m from Kassel, for fuck’s sake, where there’s the documenta art fair every five years. . And I’ve never missed a single one since 1972. Also, we spent every summer vacation visiting galleries and museums in foreign climes: throw the tent into a battered Renault 4 and off we’d go, to look at art. It perhaps didn’t rank as the greatest adventure in every phase of my youth, but that’s how it was and it did of course leave a deep and lasting impression.

HS: Many thanks, Geza.

Making of: Geza Schön and Scentury’s Helder Suffenplan. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

Making of: Geza Schön and Scentury’s Helder Suffenplan. Photo: Franziska Taffelt.

Things you should know about Geza Schön:

Legend has it that Geza Schön strode as a teenager into the HQ of perfume developers Haarman & Reimer in Holzminden, Germany, and calmly announced he wished to learn to make perfume. Impressed by this chutzpah, the company took the young man at his word and granted him a classic perfumer apprenticeship. Geza Schön became one of its most successful employees and continues to work for major houses to this day. But he wanted more.

In 2006 Geza Schön founded his own label and launched Molecule 01. This consists exclusively of Iso E Super, a molecule used generally as an ancillary perfume ingredient. To sell a synthetic molecule as perfume — and boast about it, to boot — was a scandal! Even ten years down the road, some perfumers still hate Geza Schön from the bottom of their hearts for breaking a taboo like that; or perhaps they simply envy the perfume’s sensational success: today Molecule 01 is a modern classic.